Dilution – Splitting equity in startups

Many entrepreneurs are chasing investors but the real question any entrepreneur should ask yourself is, do you really want the investors’ money?

Why shouldn’t you? Well, first of all because no investor will be giving you the money for the sake of your blue eyes – except your mum and uncle, of course. The rest want something in return – a share of the company. In startup jargon this is called ‘dilution’, when your share of the company is diluted by investors.

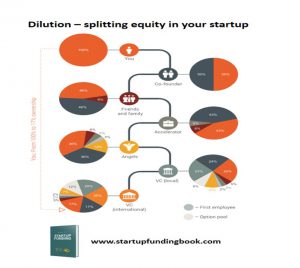

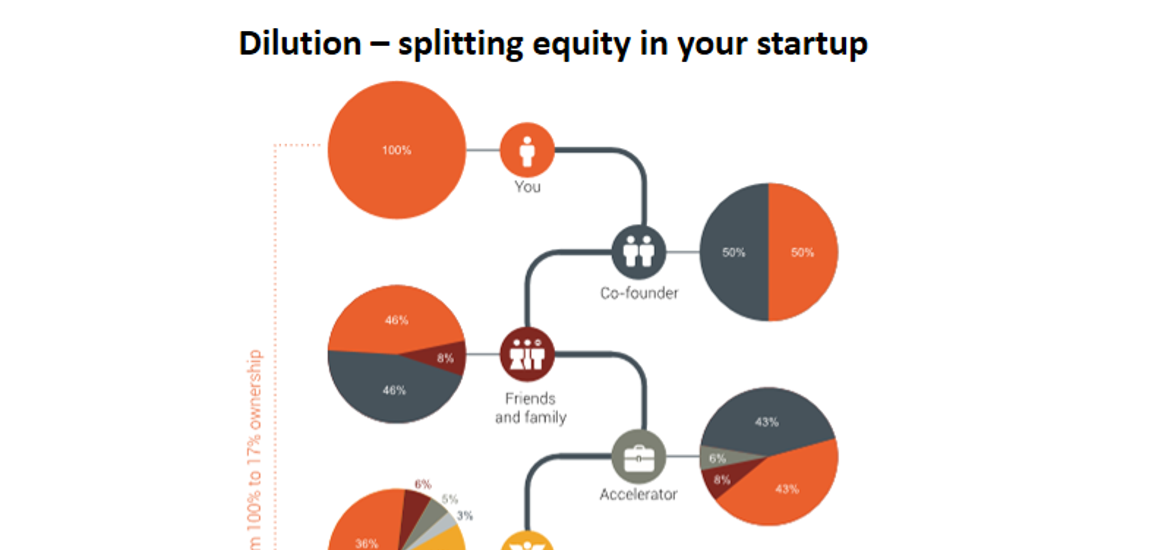

The example below illustrates a typical dilution for a company that receives funding from the usual suspects at the different stages of the company. It starts with you getting a co-founder, and having friends, angels and accelerators invest in the company. Next you give shares to the first employee and later employees in the form of an option pool, and then you receive huge investment from a local venture capital fund and later an international venture capital fund.

So is going from 100% of a very small cake to 17% of (hopefully) a large cake worth it? This depends on your specific situation and what you really want to do with your startup. Is it more important for you to be in control of your company, even if it’s a small one, than to grow it into a world-leading company? Then you certainly shouldn’t go this route! But if you have a startup where you need funding to grow, or grow fast enough, VC and other types of investors might be exactly what you need!

You should ask yourself: Do we really need the money? Will the money really make a tremendous difference for our company – or could we achieve what we want without it? And if we need money, do we need it now or could it wait till later?

It’s hard to find entrepreneurs who regret they didn’t take in external investors earlier in the journey, while it’s easy to find entrepreneurs who regret taking in investors too early when (they know with hindsight) they would have been able to bootstrap longer.

Comments

Charles F McCormick

For too many entrepreneurs, “dilution” is a four letter word (it is actually two four letter words, but I promised my editor that “no math” would be required for this article). The typical conversation goes something like this:

Me: So, what did you guys think of the offer?

CEO: We’re gonna pass.

Me: Why? They are offering a valuation of 3X your last round only about 18 months ago.

CEO: Yeah, but their offer was too dilutive.

On the one hand, the CEO is correct, but only because any issuance of additional stock is dilutive. If a company sold $1 million worth of stock at a $100 million pre-money valuation, that would be dilutive in the technical sense. Depending on the starting point, however, that might be a great deal. In my experience, confusion (and anxiety) around dilution comes from two sources.

First, it is easy to confuse dilution with industry jargon – particularly the term “antidilution.” As the terms themselves suggest, dilution and “anti”dilution are essentially antonyms. Antidilution exists to protect investors (who typically purchase preferred stock) from future stock sales of preferred stock at a lower price per share than the investors paid. (1) It refers to an adjustment to the price at which preferred stock converts into common stock if a company later issues additional shares of preferred stock for a lower price per share. As the result of such an adjustment, each outstanding share of preferred stock becomes convertible into more than one share of common stock. (2) As a general matter, an issuance of stock that triggers an antidilution adjustment is indeed a bad result for founders and other common stockholders. That said, while all antidilution adjustments (including the issuance of stock that triggers the adjustment) are dilutive, not all dilutive issuances will trigger an antidilution adjustment.

Second, the corporate concepts of “control” and “ownership” are often conflated. As a practical matter, these are distinct issues. CEOs of large public companies, for example, exercise enormous control over the companies they run, but almost none of them hold majority (or even significant) ownership stakes. Laws relating to corporate control and governance give tremendous power to a corporation’s board of directors. Corporate board composition need not – and usually does not – simply mirror stock ownership. A founder team holding less than 50% of their company’s stock may well hold a majority of the company’s board seats. At the very least, board composition is a highly negotiated issue between management and outside investors. Finally, investors familiar with the wisdom that “you bet on the jockey, not the horse” understand that whatever the formal arrangements may be, Founders should – and typically do – exert enormous influence over developing companies. More typically, investors seek to negotiate “negative” control rights that give them the ability to prevent a company from taking specified actions without their consent. Few early and growth stage investors seek to obtain operational control of a company in connection with their investment.

Despite my editor’s warnings, some math might actually be helpful here. Consider the following scenario:

$10 MM Valuation $36 MM (post-money) Valuation

Founder % 60% 48%

Investor % 40% 32%

New Investor % 20%

The above chart tells an optimistic but not unrealistic story. The above company initially raised $4 million at a $6 million pre-money valuation. It then received an additional investment of $7.2 million at just under a $30 million pre-money valuation. From the Founders’ perspective, the value of their stock increased from $6MM (60% of $10 MM) to just over $17 MM (48% of $36MM) – nearly a 3X increase! Both investment rounds were technically dilutive to the Founders (although the first round far more so than the second), but the second round would not have triggered an antidilution adjustment for the earlier investors. A realistic Board composition for this company might be 5 individuals, with three directors being nominated by the Founders, one by the first investor group and one by the second investor group.

In my experience, the big hurdle (mental, spiritual, emotional, etc.) lies at the 50% ownership threshold. As discussed above, holding less than a majority of your company’s stock does not mean that you cease to control your company. From a value perspective, the above example illustrates how it is often better to own a smaller piece of a bigger company than a bigger piece of a smaller one. Here, the Founders nearly tripled their wealth in exchange for an incremental 20% dilution. That may not always be a great deal, but it is not always a bad one either.

In summary, when thinking about dilution, please consider the following:

• Although dilution always leaves you with “less,” sometimes less really is more.

• Dilution and antidiluton are not the same thing. All stock issuances are dilutive; far less than all result in an antidilutive adjustment.

• Control and ownership are very different. In particular, control is not purely a function of ownership percentage. Also, a Board of Directors is a powerful actor in the world of corporate governance.

• In fairness, not all dilution is good, either. Valuation is a key term in any negotiations between Founders and investors. If the parties are too divergent on this issue, consider alternative financing structures, such as convertible notes.

(1) This is a critical – and frequently misconstrued — point that I hope to clarify in a subsequent article.

(2) It may be worth noting that antidilution adjustments only work in one direction. There are generally no circumstances where a share of preferred stock becomes convertible for fewer shares of common stock as a result of additional stock issuances.